Folders |

Backstage With Untold Track and Field History: The Championships, and Challenges, of Felicia GulifordPublished by

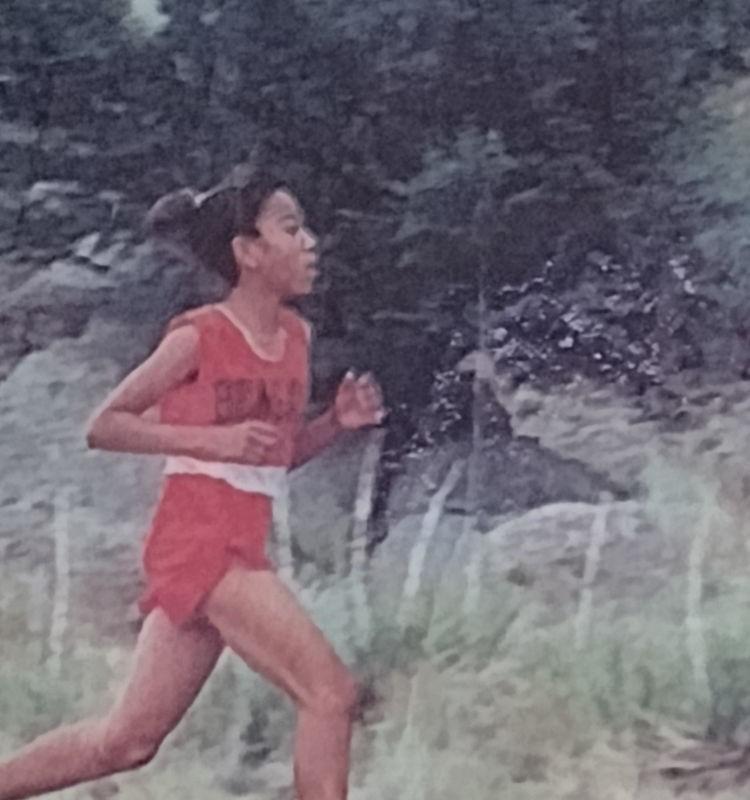

Breathless: Unraveling The Mind-Body Ailment That Prevented A New Mexico Legend 'Afraid To Not Be The Best' From Winning A National TitleBy Marc Bloom for DyeStat It was the early winter of 2000, the turn of the century, a time for renewal — a time when young runners would take stock and mobilize strength and commitment for the coming high school track season. Would Felicia Guliford even have a season? That January, a month after the 1999 Foot Locker nationals, Felicia, a sophomore at Gallup High in New Mexico, was holed up for a week with her father, Lawrence, at the charitable Ronald McDonald House of National Jewish Hospital in Denver. The medical center was renowned for its treatment of asthma and respiratory disorders. Felicia and her father could stay cost-free near campus. Day by day, Felicia would be tested by specialists to determine why she was collapsing during races while unable to breathe. Weeks before, Guliford had experienced serious breathing episodes in both the Foot Locker West Regional at Mt. San Antonio College in Southern California and the national finals at the Disney complex in Lake Buena Vista, Fla., where she’d been the favorite. In the West, Guliford collapsed while leading in the last 100 meters, and got back on her feet to place second. At nationals, same thing: leading onto the home straight with championship victory seemingly assured, Guliford wobbled and went down like a ragdoll. I was there to witness it. Shocked and well-meaning spectators yelled at her to “breathe.” Guliford rose to her feet and staggered across the line in fifth. She was then treated at the medical tent. For someone who had started running sprints as a child and begun winning high school titles in eighth grade — who ran the rugged high-altitude terrain of Gallup like she owned it — her airways calamity was a tortuous affliction, made that much worse by Felicia’s uncontrollable vomiting before races. Could the two issues — the breathing and the vomiting — be connected? Could they have the same underlying cause? Hopefully, National Jewish would provide some answers. “I would vomit before every race,” Guliford told me recently. I had covered Guliford’s national events almost 25 years ago, writing up reports in my Harrier XC magazine.

After some digging, I located Guliford now living in Texas with her husband, Eric Taylor, and their four children. Considering the medical issues that marked her youth — and her immaculate academics — it was not surprising to learn that Guliford would go on to become a physician. But instead of going into practice, she has stayed home to educate her children who are home-schooled. Her husband is a soccer coach. Guliford, from day one, has assumed the responsibility of a savior, to be the helper, nurturer, caregiver, catalyst. The shining light. Not for personal heroics but as standard bearer. “I had to be the best in everything,” she said, referring to her high school years. “I had the weight of the entire community on my shoulders.” Guliford is half Native-American, on her mother’s side, and half African-American, on her father’s. “I was born with two strikes against me,” Felicia said. Guliford absorbed the spoken, or unspoken, call to success, to be better than the privileged majority. Running history had not been kind to her people, going back to Jim Thorpe, but they prevailed. For a shocking account of how society attempted to crush the legendary Thorpe with bias and assimilation from Carlisle Indian School onward — the taking of his 1912 Olympic medals was the least of it — check out David Maraniss’ definitive biography, “Path Lit By Lightening,” which I recently read. The legacy of Thorpe and other great Native athletes like his Olympic teammate Louis Tewanina, also of Carlisle, and the 10,000-meter silver medalist at Stockholm, was ultimately inherited by none better than Billy Mills, the Oglala Sioux renowned for his spectacular 1964 upset victory in the Tokyo Olympics 10,000. Unfortunately, old attitudes die hard, and I witnessed the racist indignity shown Mills at, of all places, the very Foot Locker nationals at which Guliford competed. One year, Mills was the program’s guest speaker. His presentation was based on first showing footage of the Tokyo race, with an enervating capsule of his life story to follow. I knew Billy well and when we sat together at the awards banquet, he whispered to me his concern that the corporate bigwig assigned to announce him knew nothing of his career and would flub the intro. Sure enough, the suit blew it — it was clear he’d never heard of this guy Mills and couldn’t care less — and when Mills took the stage, the set-up for the film was in disarray and, as 64 national finalists squirmed in their seats, Mills had to overcome an embarrassing moment. In Gallup, and in the nearby reservations, the continuing fight for respect was understood. From her first jaunts up stadium steps in childhood running games, through high school and college and med school, to the creation of a self-sustaining Native community in Texas to give needy young people a new life, Guliford has symbolized the best and the brightest with relentless pursuit. The world needed saving. Someone had to do it. Guliford is a version of Doctors Without Borders. Give me your tired, your hungry, your sick. Unfortunately, under siege from her own magnetism, Guliford would get sick herself. “I didn’t know how to reach out for help,” she told me. Felicia grew up the third-oldest of four children with three brothers. The city of Gallup, with about 22,000 people, mostly Native — Navajo, Hopi, Zuni — sits on Route 66 at an elevation of 6,647 feet. For runners, you can’t do better if you’re looking for altitude training. Inspiring vistas, much of it on reservation land, greet you in every direction. In high school, on the starting line, Guliford, 5-foot-3 and 98 pounds, would have two races. The first was to the nearest trashcan to unload her breakfast. Coach Williams would try and steady her, saying in frustration, “You’re the number-one runner. What’s the problem?”

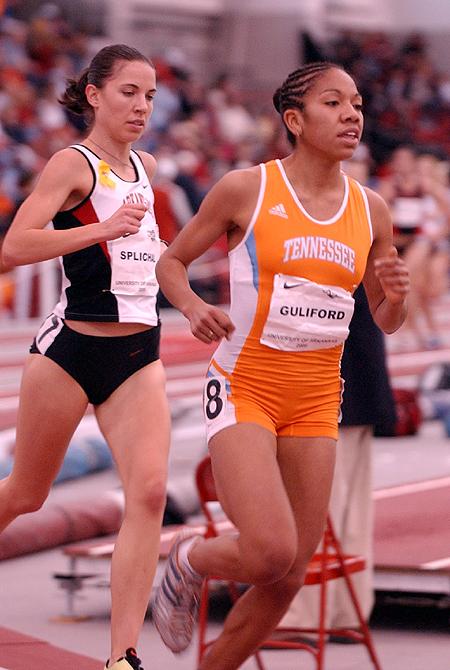

Williams, whose cross country teams collected 25 state titles, told me he’d never seen a runner push as hard. “Felicia had that drive. She had to win at all costs.” Still, top runners push hard, that’s a given. That’s desired. Williams was as baffled as anyone and concerned for Felicia’s health. The problem? Guliford had no answer for her coach other than, “I feel so sick.” Felicia’s parents were distraught, concerned for their daughter. At the Foot Locker West her sophomore season, Felicia threw up so violently before the race that her father — who’d driven 12 hours from home for the meet — felt the urge to take a picture of the refuse and affix the photo to Felicia’s bedroom wall “so she could try and overcome it.” No one seemed able to connect the dots between Felicia’s apparent anxiety and fear, and the physical symptoms. Today’s proactive awareness of the emotional distress in high-achieving young people was practically non-existent then. And there was little to go on since Felicia herself couldn’t explain it. “I didn’t know how to communicate,” she said. In addition, she told me, “A lot of people brushed it off like it was normal, just pre-race jitters.” At Gallup, Guliford took A. P. courses and had a 4.0 GPA. At practice, she ran with the boys and led the J.V. group on hill reps, 1k loops and 14x400 at over 6,500, then, once home, did her studies well into the night. In college, at Tennessee, Guliford had a 4.0 while taking pre-med subjects like cellular and molecular biology and graduated magna cum laude. She ran track and cross country all four years, was co-captain three years, won three SEC titles (indoor 3,000 and 5,000, outdoor 5,000), and took on a load of community service, earning many awards including NCAA Woman of the Year finalist. To top it off, Guliford was voted “Miss Tennessee” by the Vols athletic department. That honor recognized the female student-athlete “who best demonstrated the traits of service, leadership, academics and athletics.” At the same time, while in Knoxville, Felicia said, she developed eating issues that resulted in bone density issues that resulted in injury. Having it all — or, rather, doing it all — costs. Breathing. Vomiting. Eating, or lack thereof. The world still needed saving. Guliford found early on that she could not do it as a doctor. In medical school at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, she saw that her desire to become a healer in the broadest sense of the term was upended by a medical establishment fixated on drugs. “It was pharmaceutical medicine,” Guliford said. “I felt boxed in.” Instead, she ventured out of the box to heal. Guliford saw herself not only as a savior, but one who would achieve perfection while doing it: one who would run the perfect race, or be damned. “Felicia studied her competition,” said coach Williams, now retired and living in Albuquerque. “We’d go to a meet and she knew who everyone was. She applied as much science to running as anyone I’ve ever seen.”

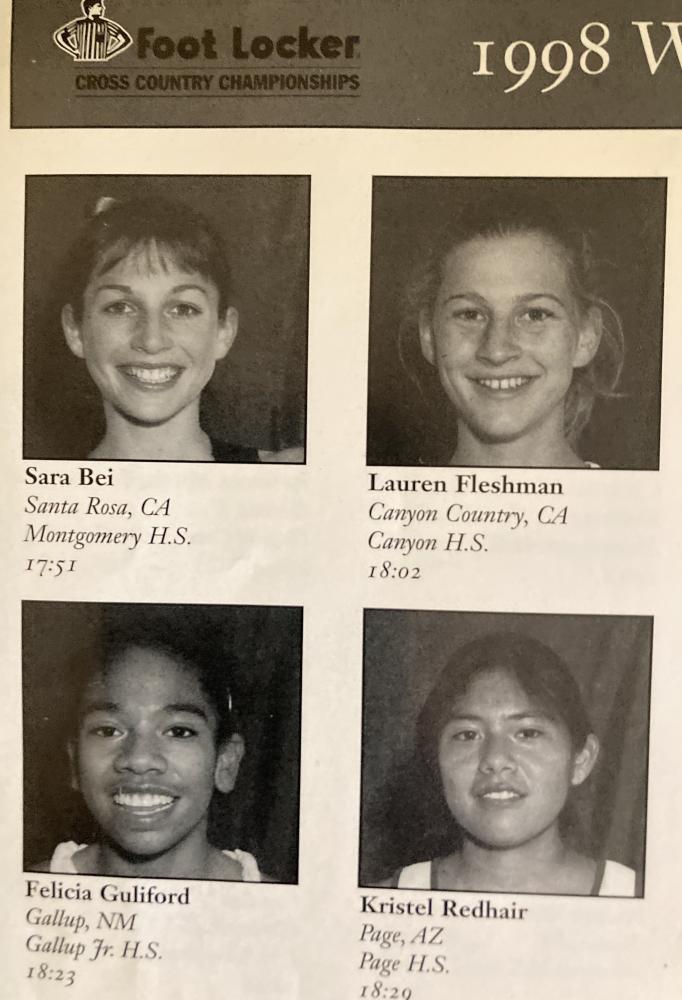

Guliford has never stopped imagining what perfect could be, what could be pure and righteous. In recent years, Felicia has worked with her husband and church groups to minister to a Native children’s home in Gallup. At first, while they were living in Virginia, this endeavor involved fund-raising and mission trips back to Gallup. In another humanitarian task, Guliford, using social media, advocated for early treatment of COVID-19, helping numerous people and saving lives. Now, living in Texas, Felicia and her family are homesteaders on a 20-acre plot of land midway between Austin and Houston in a barren place called Old Washington. Picture the landscape in a Cormac McCarthy novel. Currently, the couple and their four children live in an R.V. while waiting for ground to be broken for a new home. When they put down roots two years ago, there was nothing, not even a road. No electricity or running water. “We started from the ground up,” Guliford said. They grow their own food. They harvested, canned, planted and replanted. They worked the land even in the summer heat of 108 degrees. Felicia and Eric wanted their children to learn self-sufficiency. They gave them names that reflected the sacred-ness of nature: Lake, Storm, Sage and Sky. Eric dug out a trail so Felicia could run. She does three to four miles a few times a week. Threaded into the Gulifords’ Thoreau-like worldview was an ambitious master plan: to take the concept of the Native sanctuary they’d created in Gallup and expand it on their Texas property with 20 homes, an acre each, for young people to get a start in life. “Many people come out of foster care with trauma. We want to give them a safe place.” If you can’t quite save the world, bring the world to you. “It’s a dream of ours,” Guliford said. When we spoke, I got the sense that Felicia, nearing 40, was still coming to terms with her earlier affliction; that even with her medical expertise and years of reflection, she was not quite sure how, under the stress of racing, the interplay of mind and body could produce such devastating trauma. Her running began as a child with her father coaxing Felicia and her brothers to run up a hill and roll down. They used stadium steps to learn coordination. They sprinted 20, 30, 40 yards. “I made fun out of it,” said Lawrence Guliford, a high school Special Ed teacher. “To learn how to set your mind and accomplish something.” Guliford set an example himself. He’d been a sprinter at Eastern New Mexico University, a program best known for nurturing the Kenyan Olympian Mike Boit in the 1970s. After getting his feet wet in distance running, Guliford would do 20-mile runs on a weekend while his wife, Edna, an art teacher, along with Felicia and one or more of the boys, would follow him in an old Dodge van, handing him drinks. “We thought Dad was crazy,” Felicia said. “We didn’t even like to drive 20 miles.” It took the father close to four hours to run and three days to recover. Afterwards, he ate everything he could get his hands on, feasting on Edna’s spaghetti-and-meatballs. “I wanted the kids to see what their daddy could do,” he said. Felicia liked the idea. But let’s keep it short, please. In a sixth-grade field day, she won the 100, 200 and 400. Coach Williams was watching, his scouting impulse sharp. He introduced himself. Felicia was all of 4-foot-2 and 60 pounds. “I said, ‘How would you like to run cross country in high school?’ She said, ‘What’s that?’ I said, ‘You train three to seven miles a day in practice and the races are 5k. We’ll break you in.’” Hearing this, Felicia struck a sassy pose with hands on hips and a tweeny attitude and declared to her future mentor: “I’m a sprinter.” Williams convinced Guliford to give cross country a try. He got the school board to change the rules, allowing eighth graders to run varsity. That fall of 1997, Guliford was undefeated during the regular season with a second in the state 4A finals, leading Gallup to the team championship. But her destiny was unveiled when, as Williams put it, “she threw up her cookies before the race.” Her freshman year she was also undefeated and then won her first state cross country title, by 34 seconds. Wherever her cookies may have landed, in December Guliford ran her way into the Foot Locker nationals, the only freshman to do so that season. Foot Locker seems never sure of what it should be called or where it should be run. Its name has changed several times and is now back to Foot Locker, which is what most people call it anyway. The program finals started in Orlando in 1979, then switched to San Diego the next year, then re-planted at Disney’s flat golf course in 1997 before going back to San Diego in 2002. In 1998, Guliford stuck her freshman nose in with the leaders, despite terrain that was new to her, and wound up fourth as girls from the West captured five of the top 10 spots. “She’s never run on grass,” Williams told me afterwards. “We’re in the desert. We run on rocks and dirt.” Guliford ran the Disney course almost two minutes faster than she had while winning her state meet on one of the hardest courses anywhere, Gallup’s Red Rock Park. Erin Sullivan of Vermont grabbed a repeat nationals triumph with room to spare. The next two girls ahead of Guliford were future professional stars from California: five-time NCAA champion Lauren Fleshman, and the sophomore Sara Bei, who would become one of the world’s leading marathoners. Guliford’s roommate was another Native girl, Kristel Redhair, a junior out of Page High in Arizona, whose mature presence gave Guliford comfort in the threatening white environment. “I leaned heavily on her,” Felicia recalled. Fleshman and Bei were also good-natured and generous, so much so that the California pair enlisted Guliford and Redhair in a defiant act of Foot Locker bravado. Heck, call it a prank.

Laughing: a good sign. Would that it last. Guliford got through her freshman year without a serious respiratory episode. The big time was still new to her, like a cloud ready to burst. She was the Broadway understudy poised for a starring role, and with it the turbulence of whipsaw emotions. In her sophomore year, Guliford was in demand. A new in-season event in North Carolina with national aspirations was starting and the founder, a southern businessman named Rick Hill, wanted Guliford for his meet. My Harrier XC team rankings, begun in 1989, were the catalyst for Hill’s plans, which he’d discussed with me for months prior. Hill invited top-ranked teams, and some individuals, with offers of expenses paid, and many took him up on it. The late September affair was called the Great American Festival, whose ownership later passed to the National Scholastic Athletics Foundation. That first year it was held at McAlpine Greenway, in Charlotte, the Foot Locker South Regional course; eventually, the meet re-located to the WakeMed fields outside Raleigh. In 1999, teams from more than 20 states including California competed in what amounted to an almost-mid-season assessment of national prominence. High school cross country seemed boundless, as Nike Nationals would show again five years hence. Alan Webb of Virginia was the rock star entry. A junior, he’d run a 4:06 mile as a sophomore, at a time when that was still pretty fast. He would win by a stride in 15:04 for the fast 5,000-meter route. The boys team championship went to The Woodlands of Texas over Christian Brothers of New Jersey with Bingham of Utah third. All three were national powers. Gallup's boys and girls teams made the trip. Williams finessed his leverage with Guliford like a pro track agent to get the whole party paid for. Guliford and her teammates were star struck. It was the first flight for most of them, the first hotel. Guliford felt as ease, and when Williams told her she could win, the course was easy, you’re coming down from elevation, she believed him. With a half-mile to go, Guliford pulled away from a pair of twins from team winner Bingham UT to take the title by 13 seconds in 17:13. Guliford had defeated top girls from Utah, Wyoming, New York, Virginia, Florida, Ohio and Texas. In my Harrier XC mid-season report, I ranked her No. 1 in the country ahead of Bei and a promising girl from the Boston area — the future all-time great Shalane Flanagan. “That was heavy,” Guliford said, as though it was yesterday. After Charlotte, she bit her lip. She took deep breaths. She would need them. Back in Gallup, the limelight cast its shadow. Before one meet, Guliford almost threw up all over coach Williams, who was trying to liberate his star from doing damage in a port-a-john with her race about to go off. To try and arrest her breathing issues, Guliford employed an elaborate treatment regimen. A half-hour before warming up for races (and after as well), she would take a medicated inhaler, breathe through a portable steam vaporizer and wear a sealed surgical mask — all to keep her airways open. “My teammates called me Dr. Guliford,” Felicia told me then. Smart kids. When Felicia did her morning runs at 5:30 in the darkness, her father trailed her by car. With the fall chill in Gallup, Felicia wore the facemask to contain warmth. She looked like an alien that had climbed out of a UFO in the New Mexico desert. After Great American, Guliford was the Foot Locker favorite. How much pressure could she stand? Did she need a facemask, metaphorically, to keep the demons away? At Mt. SAC, at the aforementioned West Regional, Bei led most of the way until Guliford pulled ahead off the final hill and approached the finish on the track. Soon she was literally on the track. Alicia Craig won while Bei faded to a non-qualifying 10th (eight runners from each region made nationals then). “It was very sandy,” Guliford told me at the time. “It was flying in my face, which triggered the asthma.” Her father had witnessed this latest calamity, still of uncertain origin. He told me, “We were trying to figure it out: was it a panic attack, or asthma, or…?” One thing he was sure of, his daughter always ran to the limit. “Like Prefontaine,” he said. Amid the concern and confusion, Lawrence Guliford could only do what any parent would do. He enveloped Felicia in a hug and told her, “Daddy loves you.” At Nationals, while the boys’ championship saw Dathan Ritzenhein, a junior from Michigan, capture the first of his two titles — Ritz would go on to make three Olympic teams and become a top professional coach — the girls’ race would revolve around the diminutive runner from New Mexico: was Guliford healthy, hindered, psyched out, or just plain wasted from all the stress and frustration? Could Dr. Guliford manage to breathe normally for 17 minutes or so? Could she use her red blood cell enriched oxygen from training 60 miles a week at sky-high elevation and, as coach Williams had said, come down to sea level and handle any pace with aplomb? She’d done it in Charlotte. On the eve of the race, 12 weeks later, Guliford had never been fitter. One workout had taken her way out to the Navajo Reservation and past Superman Canyon, so named because the actor Christopher Reeves flew through the Navajo air while filming the 1978 “Superman” movie. The Superwoman couldn’t stop being hard on herself. After the West Regional, she’d told her mom, “I had the race won but I blew it.” Would a reckoning occur? Running among the leaders at nationals with a half-mile to go, Guliford pulled ahead, a well-tested strategy. Craig was gapped in second with Victoria Chang of Hawaii, third at the regional, close behind. If Guliford needed to kick, she had the tools. Her training included a dozen 200s in under 30 seconds. Chang was composed. No one had paid her much mind. A Punahou senior, she’d run mostly 2-mile races on the Islands, and had made a three-legged, 12-hour journey to the meet. Her coach wasn’t even there. Duncan Macdonald, former American record holder in the 5,000 meters and an anesthesiologist, could not leave patients to make the trip. It turned out, Chang didn’t need much, just the inevitable demise of her overwrought rival, the front runner. With 100 meters to go and now in view of the boisterous finish area crowd — amid all the fanfare of the event’s 20th anniversary and whirlwind Disney weekend — Guliford began to wobble, lose her balance, bend over and try not to fall. Finally, she would go down. A stunned Chang rushed to victory in 17:06. Crushed, and lain on the ground like a marathoner who’d hit the wall, Guliford gathered herself and finally rose to her feet, staggering across the line in fifth, 24 seconds behind Chang. Guliford’s mother watched. Her father, at home in Gallup, called the Denver hospital. Once there, Guliford’s cardiac and respiratory functions were tested daily: on a treadmill, bike, in a swimming pool. Nothing definitive was found. Only when a sport psychologist intervened did it seem apparent that Felicia was not felled by classic asthma but by anxiety that contributed to her breathless attacks. The therapist worked on improving Felicia’s breathing mechanics by strengthening her diaphragm. He would place a book on her stomach while she was prone, and she would practice deep breathing for 30 to 60 minutes. Another time, at a rehab center in Texas with coach Williams present, Guliford was told likewise: when impacted by emotional turbulence her diaphragm faltered, deflecting its function upwards to the chest, constricting her airways. Still, nothing concrete was done about her anxiety per se, and in her junior cross country season, Guliford collapsed twice at the West Regional, dragging herself across the finish in 72nd place. Could things get any worse? They got better, at least for her senior year. Guliford rebounded to take second at the 2001 regional and sixth at nationals in her third try, as the record-breaking Amber Trotter of California triumphed by an unprecedented 50 seconds. Was Felicia’s stronger diaphragm finally paying dividends? Hard to say. In our conversations at the time, Felicia gave me one more explanation that had come to her — vocal cord dysfunction. “During running,” she said, “my vocal cords stuck together and I couldn’t breathe.” Looking that up now, I see that the condition is described as a restriction of the airway upon inhalation that causes the gasping sound of someone “exercising heavily.” The literature also states that the condition can be triggered by anxiety and, according to a fascinating point in a 2021 Runner’s World story, “women and academic high achievers seem to be more susceptible than the general population.” The article does not say why that may be so, but in Guliford’s case I think it’s clear that in the mind-body mosaic of her hard-fought constitution, anxiety had been the culprit all along. From my own considerable study of psychology, I would also suggest that Felicia had some conflict over her strivings, that, deep down, she probably resented, at times, the compulsion to be the “perfect Indian girl.” Guliford took her inner turmoil to college, in a sense trading one impairment for another, a common emotional dynamic when reality is hard to bear. While leaning toward Stanford, she and her family decided instead on Tennessee, when the Vols’ head coach, J.J. Clark (ironically, now director of track and field and cross-country at Stanford) came to Gallup on an up-close-and-personal recruiting visit. He’d been prompted to make the trip by his wife, Jearl Miles, the 1993 world champion in the 400 and former American record holder in the 800, who was very high on Guliford.

“People asked if I lived in tee-pees,” she said. “I was shaking.” While Guliford was half-black, and there were black athletes on the team, Guliford said she hadn’t known black people in Gallup, and was more comfortable, at first, with the white girls on the squad. “I had to navigate a fine line,” she said. Guliford became close with a white teammate from Lubbock, Texas, Mindy Kate Sullivan, whom she’d run against twice in high school. Sullivan was an 800 specialist with the second-fastest time in the country as a junior in 2001, 2:08.38. Sullivan won that year’s Great Southwest 800 as Guliford took third in a PR 2:14.54 while winning the 1,500 in 4:43.99. Sullivan also made the 2001 Foot Locker nationals, placing 17th. Guliford and Sullivan, who are still friends, clicked on their feelings of dislocation. “I knew so many Hispanic people in Texas,” Mammen (her married name) told me, when I reached her at her Washington, D.C., office, where she works in banking. “In Knoxville, everything was different and leaving the nest was a challenge.” At that time about 20 years ago, college track and cross country’s dirty little secret were the large numbers of women who had disordered eating or full-blown eating disorders, as thinness was conveyed in one way or another as the ideal. Runners who were unhealthfully thin with too little body fat usually did not get their periods because a certain level of fat is necessary for menstruation. Consequently, they did not produce the hormone estrogen, essential for bone building, and were at increased risk of injury. This was commonly called the “female triad” and is now often referred to as RED-S, relative energy deficiency syndrome. Either way, it means an athlete simply is not taking in enough fuel to maintain good health. Guliford told me she never got her period in college and suffered a stress fracture and other injuries, similar to her junior year at Gallup. Still, even with all the demands on her time in Knoxville, she would turn up at practice to cheer teammates. “Felicia was so animated,” recalled Mammen. “She shared her love of running with everybody.” At meal time, Felicia ate only salad. She was not the only one. “It was contagious,” said Mammen, who recalled a teammate who ate nothing but lettuce for lunch and dinner. If a woman lost weight, Mammen said, she would hear, “You look so fit,” when it should have been, “You look so sick.” Guliford understood what was happening but could not gain control of her weakness and the conflicts that served it. “I tried to eat more,” she said. “I just couldn’t.” When I brought the situation up with Clark, he said, “I always addressed eating well to stay healthy.” I have no doubt that he did. But there was a pernicious cultural imperative at work on many women’s teams then, often beyond the capacity of the coach to comprehend or reel in. Women learned to mask their problems, which perhaps they themselves did not understand at a time when so little was known about the ailment. “We had one teammate who starved herself,” Mammen said. “She learned the trick of shoving a toothbrush down her throat” to eject food. Guliford told me, “If I’m going to be honest, most of those in the freshman class had eating issues, but no one talked about it.” Mammen said the nutritionist on staff was not helpful. “She did not understand the female distance runner. We would have meetings and she would say, ‘You can have three cookies at lunch.’” Is the female distance runner truly understood today, when psychological counseling on campus is readily available? Based on the pressures young women still feel and often talk about in blogs and books, one would have to wonder. After college, and medical school, Guliford could start to free herself from the bonds of performance and throw her abundant energies into her children and the needy, where, in a way, her place had always been. “Felicia exudes joy,” Mammen said. “It’s rooted in her religious beliefs and moral foundation.” Today, looking out onto the great expanse of her land, Guliford is filled with promise. Thinking back to the difficult moments, she reflected: “I was so fearful of striking out, of disappointing anyone. I was afraid not to be the best.” Guliford paused as though surprised by her realization, not as someone who’d mastered molecular biology but as the little girl grown up, finally at peace. She said, “I didn’t know then that my thinking could bring about a physical reaction, that my emotions could make me sick. You’re the first person I’ve ever said that to.” # The journalist and author Marc Bloom contributes long-form stories on track and field and cross-country history periodically. His books include Amazing Racers, about the Fayetteville-Manlius dynasty, and God On The Startling Line, about his coaching experience at a Catholic school. Last year, Marc was inducted into the Van Cortlandt Park Cross Country Hall of Fame. More news |

I remembered Guliford fondly and knew that her coach at the time, Curtis Williams, was among the best. When I checked back on my old Harrier XC issues, I was stunned to remind myself of the severity of Guliford’s condition, and keen to find out about her life since.

I remembered Guliford fondly and knew that her coach at the time, Curtis Williams, was among the best. When I checked back on my old Harrier XC issues, I was stunned to remind myself of the severity of Guliford’s condition, and keen to find out about her life since.  (DyeStat archives)

(DyeStat archives)

One night, after lights out, the four left the hotel unchaperoned, expressly forbidden, and… well, I can’t say what transpired because Guliford, sworn to secrecy, would not spill the beans even after 25 years. She would only say: “It was a dare. We laughed and laughed the entire night.”

One night, after lights out, the four left the hotel unchaperoned, expressly forbidden, and… well, I can’t say what transpired because Guliford, sworn to secrecy, would not spill the beans even after 25 years. She would only say: “It was a dare. We laughed and laughed the entire night.” Upon arrival in Knoxville, Guliford experienced what she called a “cultural earthquake” in the predominantly white community. Nothing was like Gallup, including her mom’s corn stew.

Upon arrival in Knoxville, Guliford experienced what she called a “cultural earthquake” in the predominantly white community. Nothing was like Gallup, including her mom’s corn stew.